By ROD McGUIRK | Associated Press – Sat, Nov 29, 2014 12:30 AM SGT

CANBERRA, Australia (AP) — Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott, who rose to power in large part by opposing a tax on greenhouse gas emissions, is finding his country isolated like never before on climate change as the U.S., China and other nations signal new momentum for action.

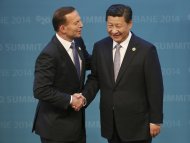

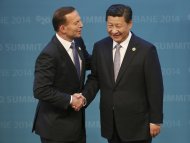

Abbott tried and failed to keep the issue off the agenda of the annual G-20 summit of wealthy and emerging countries that was hosted by the Australian city of Brisbane in mid-November. An agreement between Washington and Beijing to curb emissions, announced days before the summit, suggests he had misjudged the international mood on the issue.

Next week, attention turns to the next round of international climate change negotiations in Lima, Peru. For a nation of just 23 million, Australia has played a significant role in past talks, but this time it’s unclear what kind of role its delegation, led by Foreign Minister Julie Bishop, will play.

Abbott’s conservative coalition won a landslide election victory last year over the Labor Party, which had grown unpopular in part because it had approved one of the world’s highest taxes on major carbon gas polluters. Abbott not only ended that tax but years earlier helped scuttle an effort by his own Liberal Party to reach a bipartisan deal on a carbon-trading scheme, intended to encourage industries to produce less emissions.

G-20 heavyweights including the United States and Europe steamrolled Australia’s efforts as summit host to keep climate change off the agenda in Brisbane. In the end, the G-20 agreed to work together toward a global agreement on reducing carbon gas emissions at a major U.N. climate change conference in Paris in September 2015. The Lima meeting is the final high-level ministerial summit in which countries will aim to work toward a draft agreement to be presented in Paris.

A European Union official described getting Australia to agree to the wording of a paragraph on climate change in the G-20 summit communique as slow-moving “trench warfare.” In arguing for keeping climate change off the G-20 agenda, Australia said it was not strictly an economic issue and would distract from goals including a plan to boost global GDP by more than $2 trillion over five years.

President Barack Obama miffed some in Abbott’s administration when he said that among Asia-Pacific nations, “nobody has more at stake when it comes to thinking about and then acting on climate change” than Australia.

“Here in Australia it means longer droughts, more wildfires. The incredible natural glory of the Great Barrier Reef is threatened,” he said.

Bishop said she was “surprised” by Obama’s speech and later wrote to him, outlining Australian measures to protect the World Heritage-listed coral reef and assuring its preservation for generations to come. The Labor opposition described the government’s response to the speech as petulant.

Obama also used his speech in Brisbane to pledge $3 billion to the Green Climate Fund, a U.N. initiative set up to support developing nations dealing with rising seas, higher temperatures and extreme weather events.

A previous Australian Labor Party government played a leading role in establishing the fund, which has received close to $10 billion in pledges from more than 20 countries. Australia has not offered money to the fund, though it says some of its foreign aid budget is spent on climate change mitigation.

Swedish Climate Ambassador Anna Lindstedt, who will be part of her country’s delegation in Lima, said Australia’s reluctance to contribute to the fund has created a “negative dynamic” in negotiations with large developing countries including China, who ask why they should be expected to contribute when Australia, one of the richest countries per capita, won’t.

“Their climate negotiators are still doing a very good job and trying to be as constructive as possible, but it is a challenge under the current circumstances,” Lindstedt said. “Some emerging economies are in some ways more progressive than Australia.”

On the sidelines of the Brisbane summit, Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu said global warming would be a top-agenda item when his country hosts the next G-20 leaders’ summit at Antalya in 2015.

“The biggest challenge to all humanity today is climate change,” Davutoglu said. Abbott’s staff later snubbed Davutoglu’s request for a photograph of the two leaders together to represent the presidency of the G-20 changing hands.

Abbott said after a recent meeting with French President Francois Hollande that it is “vital” that the Paris climate change conference succeeds. He added, “For it to be a success, we can’t pursue environmental improvements at the expense of economic progress. We can’t reduce emissions in ways which cost jobs.”

Nic Stuart, a columnist for The Canberra Times, wrote this week that because of Abbott’s doomed effort to keep climate change off the G-20 agenda, “a vital opportunity to jump-start his prime ministership with some international pizazz was squandered.”

Abbott’s popularity in opinion polling is at a record low for a first-term Australian prime minister. Key planks of his first budget, widely condemned as unfair to the poor, remain stalled in the Senate.

Climate change was the issue that brought Abbott to the helm of his conservative Liberal Party in a leadership ballot of lawmakers by a single vote in 2009. His predecessor, Malcolm Turnbull, was deposed over his plans to support the then-ruling Labor Party’s legislation to create an emissions trading scheme.

Abbott is known for saying, also in 2009, that the “climate change argument is absolute crap.” He later said the comment was “a little bit of rhetorical hyperbole.”

This July, Australia became the only country to toss out an existing carbon-pricing system when Abbott’s government repealed a carbon tax levied on the nation’s 350 worst industrial greenhouse gas polluters.

Instead, the government has created a 2.55 billion Australian dollar ($2.2 billion) fund of taxpayer money to pay industries incentives to become cleaner. Abbott has ruled out any polluter-pays options for reducing Australia’s greenhouse emissions, which on a per-capita basis are among the world’s worst.

Abbott’s government says its policies can bring the country’s carbon gas emissions to 5 percent below 2000 levels by 2020.

Erwin Jackson, deputy chief executive of the Climate Institute independent think-tank, is doubtful. He said he hopes the Australian delegation in Lima agrees to contribute to the Green Climate Fund and proposes a credible plan to reduce Australian emissions post-2020.

“The challenge for them is that they don’t have a sustainable or credible climate policy in Australia,” Jackson said.

___

AP writer Karl Ritter contributed to this report from Stockholm.